Reflection: Living Matthew 25

Reflection: Living Matthew 25

“When the Son of Man comes in his glory, and all the angels with him, then he will sit on the throne of his glory. All the nations will be gathered before him, and he will separate people one from another as a shepherd separates the sheep from the goats, and he will put the sheep at his right hand and the goats at the left. Then the king will say to those at his right hand, ‘Come, you that are blessed by my Father, inherit the kingdom prepared for you from the foundation of the world; for I was hungry and you gave me food, I was thirsty and you gave me something to drink, I was a stranger and you welcomed me, I was naked and you gave me clothing, I was sick and you took care of me, I was in prison and you visited me.’”

Matthew 25:31-35

I am writing from Baltimore, a truly lovely town. It has been a great blessing that the PC(USA) is holding several events in Baltimore at this time—first, Big Tent which just finished, then the Mid-Council Leaders will gather here in October and of course General Assembly will be held here in June 2020.

I am actually here thanks to the Presbyterian Mission Agency (PMA) Board, who invited a select group of presbytery executives and all the synod leaders to give their perspective on priorities for the PMA. Some of you may remember that my term on the PMA Board ended at the 2018 General Assembly, and I have greatly enjoyed moving from Board member to frequent participant in this year’s trend of consultations.

The 2018 General Assembly affirmed the Matthew 25 movement, and Diane Givens-Moffett, the new President and Executive Director of PMA, has adopted this as the guiding vision for all that PMA does. She knows not to call it a program or initiative, because she’s heard that the last thing the church wants is yet another new program that has to be discussed for possible adoption, implementation, or rejection, only to have the next GA move on to something else. But Matthew 25 is so indicative of Jesus’ gospel that PMA is confident that it is a worthy challenge for all of us, at all levels of the church. So churches, presbyteries, and synods are also being invited to commit to being a Matthew 25 church as well.

(This actually has caused some confusion for us in Southern California, where the Matthew 25 movement has already been established, especially focused on immigrant welcome. You may remember that our keynote speaker at this year’s WinterFest was Alexia Salvatierra, who is the leader of Matthew 25/Mateo 25 SoCal. Kristi Van Nostran is working on an invitation that addresses both Matthew 25/Mateo 25 SoCal, and Matthew 25 for PMA. The PMA version is much broader than Matthew 25 SoCal, but we are likely to continue to keep immigrant justice as the focus of our efforts.)

So Diane has developed a Bible study of Matthew 25 that I found very compelling, and I hope that she will come to Southern California to share it with us. I wanted to highlight just a couple of things as a preview.

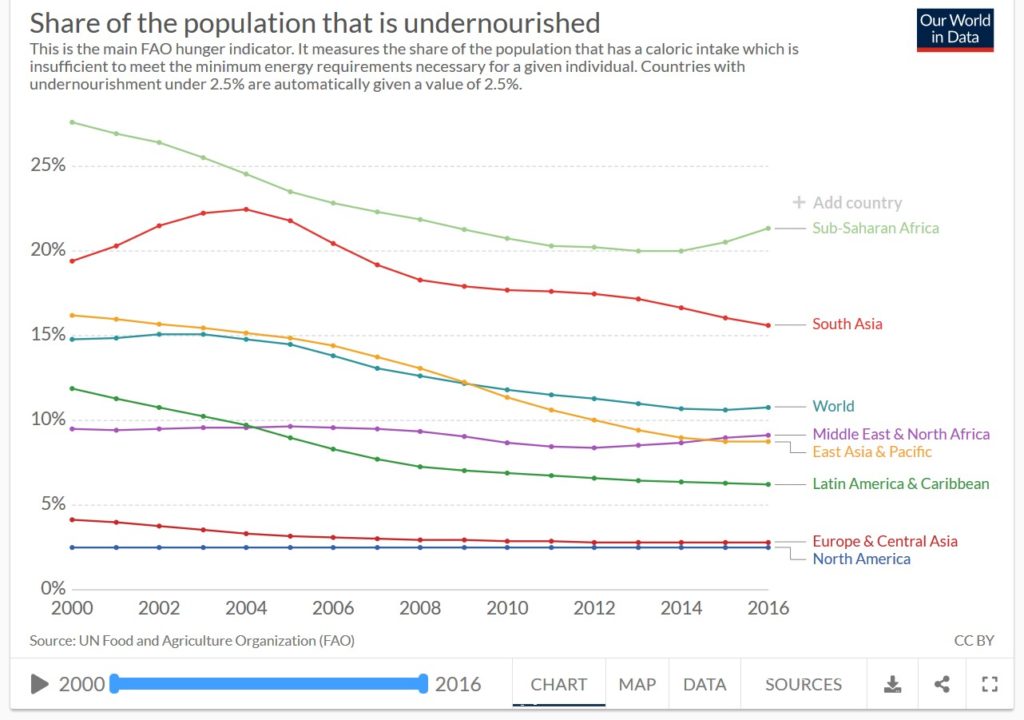

First is one of those things that are obvious if we read the whole scripture passage rather than cherry pick the most convenient parts. We North American Christians have a habit of privatizing our faith, so whenever there’s a call to mission we tend to assume the call is to us as individuals. But the beginning of this passage clearly addresses “the nations”—so Diane pointed out that this is not just a call to each of us to feed the hungry or welcome the stranger, it is a call to the nations to do so. This is why we in the Reformed tradition do not limit our vision to our own personal efforts, but we call on the nations to address systemic injustice. Yes, we can give a meal to one homeless person on the street, and yes, we can have a food pantry at our church. But also, yes, we can call on our nation and all nations to eradicate hunger, knowing that it is possible with the resources of the earth, if we chose to distribute the food to all. The good news is that even in recent years, hunger and poverty have been reduced in countries like China, India, and Kenya, though there is a direct correlation between increases in hunger and conflict and impacts of climate change.

But I digress. Diane didn’t get into world hunger statistics, but she did give a very helpful chart of the systemic ways our nation can respond to the needs of our siblings in Christ:

- Treatment of the hungry (access to land)

- Treatment of the thirsty (access to clean water)

- Treatment of the stranger (new arrivals)

- Treatment of the naked (vulnerable persons)

- Treatment of the sick (access to health care)

- Treatment of the prisoner (access to justice).

So yes, we can work person-to-person, and it’s important that we learn to relate to individuals in need and see them as cherished children of God. But we can also work to advocate for systemic change. Amidst all the terror around us, we have seen proof that there can be systemic improvements in feeding the hungry, supplying water to the thirsty, caring for the refugee, defending the rights of the vulnerable, providing health care to all, and reforming our justice system.

This last weekend has seen the epidemic of gun violence exploding in more communities than we can keep straight. But there was also a time when global hunger seemed a permanent condition. There can be systemic change, for the sake of millions. We have also seen nations and even states that have been able to curb gun violence, if only the leaders have the will to confront it. So we must not lose hope. May we continue to work in faith, without fear of what the world might think. Instead, let us trust that if we do our part, God will magnify whatever efforts we offer.

In faith and in trust,

Wendy